A sideways look: Origins of ‘art’, ‘artists’ and the ‘art market’

So, tell me again; where are we going with this …..?

We invite you to cast your mind back a while and let your imagination run alongside your sense of humour…..

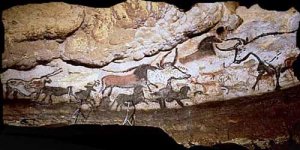

The Cave of Lascaux, what really happened?

About 32,000 years ago, when someone, a child or a youth perhaps, drew images on the rock face in the Cave of Lascaux it probably generated a number of responses, each recognisable today: (a) from the mother, a social rebuke for ‘drawing on the walls’ of the bedroom, (b) from the father, a remonstration, “what is it for” and “shouldn’t you be out doing a job or, at least, something useful”, (c) the cave’s ‘Shaman’ reached an understanding that, contained therein, there was great potential for communication and data management in terms of society and the belief system, control of which must be taken over by his profession, (d) a request, through her agent – EEEBayee – from the Chief’s wife that “it would look nice in my new kitchen”.

That particular cave was one of a complex in which three ‘communities’ lived: to the ‘left of centre’(?!), another group had set out to live a different life based on non-violence and a vegetarian diet. Their ‘Shaman’ decided the drawings were too linear and non-representational of real herds. Worse, especially amongst the emergent ‘feminists’, because almost everything ‘drawn’ was male, the whole thing was a crude metaphor for a penis and the hunt scenes represented male dominance, typical of the genre of a ‘ladlit culture’ which was unacceptable to the modern Neanderthal mind.

‘To the right’ (?!), in the other cave, another group had formed, sharing ideas and experiences to ‘learn’ from each other by ‘internal telling’ – or intellectuals for short. They had fashioned vines and bamboo to make pulleys with which they had hugely increased their ability to haul stocks of food and fuel ready for the long winter. They intended to trade their surplus and store the resultant funds ‘offshore’ aka. Safely in the hollow bank at the back of the cave. This gave them – leisure time – in which to devise a high-tech development of the drawings they had seen.

The third group, living at a level above the other two, ‘the techies’ – or New Mediarists as they were called at the clan gatherings, because, technically, nothing worked when they tried to demonstrate their powers – had conceived the idea of putting the; drawings’ onto individual pieces of rock, aka ‘pages’, and then ‘binding’ them together in strict order so that the pictures could be ‘accessed’ by turning each piece of rock (i.e.’ the page’). But it was felt by most that this would never work. The end product, referred to by its working title ‘a book’, was cumbersome and immensely heavy, even for a Neanderthal. And so, it was considered amongst the deep thinkers that, the experience of accessing the media in this form would be unlikely to replace the pleasure of curling up on a pile of hides and watching the drawings on the wall flicker by the light of the communal fire.

It is worth recording that one individual had left the area, covering his head, as the rest threw at him the rocks, that he had suggested were themselves actually the real content – ‘the artistic object’ – and not the outdated images with which others had defaced their surface.

Each new development in creativity has been questioned in terms of belief systems, social relevance, comparison to previous work and the value attached to it, both in general and related to specific pieces by specific creators. That is why we have, of late, been asking ourselves: what is the future of ‘art’: where is it all going?

Some established professions that are germane to our creative activities, such as agents and publishers, architects, accountants, engineers, lawyers – bankers even (unlikely though that sounds) and the rest, are rethinking their future(s) in terms of making both a contribution and a living in the face of rapidly developing technology, including AI.

Equally, many ’artists’ must be, or should be, asking themselves the same question. One wonders, what contribution might our friends at Grammarly, Atticus, Reedsy and the like – and who knows change might even reach Kindle – help the creative writing community achieve in terms of formatting and publishing and reaching out to our audiences.

If on the day the Fighting Temeraire arrived, JMW Turner had possessed a smartphone – or if Gaugin had one in his haversack in Tahiti when he was painting When will you marry? – how might they have represented the image or used their colour palette? What do we think might have emerged on their canvases, at a time when the economic structure, at its extremes, left the artist dying in poverty in a garret – only for his/her work to be sold 100 years later for millions of pounds?

So then one asks: why should that be so? Is it aught to do with talent and intrinsic values? Or is it the ‘voice of market forces’ driving the tongues of ‘supply and demand’ amongst a privileged few amongst whom possessing objects of artistic rarity and/or beauty is oftentimes all that matters?

In terms of our interests here at theCafé, we shall continue to explore what might be the future relationship between capturing and then reimagining an image.

Some of the technologies to which we refer in theCafé and which we are embedding, used to be called ‘New Media’ by academics and ‘users’ alike. Whatever we now like to call them, here at theCafé we think of them as a ‘toolbox’, a set of aids that allows us, people, to explore the range of human senses more fully, more openly and more quickly than ever before.

The dimensions of imagination, vision, touch, sound, and smell can be approached by creative practitioners with more confidence and competence than ever, and the vast range of human ideas and aspirations can be dissected, re-assembled and presented in almost any form we/people choose.

Moreover, these capabilities come at a time when people can reach out and locate almost any person, place or thing on much of the planet. More importantly, we can, in moments, ‘bring people together’ and create conditions for sharing ideas and aspirations. In the past decades, an evolutionary process has followed every major technological advance – cars, trains, planes, computers, TV, and phones – all elements of communication get better whilst remaining, in essence, what they were. The performance and capabilities of these innovations and products may improve as to be barely recognisable, but their basic function remains.

Arguably, many debates about ‘technology’ in this context are, largely, based on uncertainty about its function – is it a toolbox or something new in its own right? The other big question, and it is getting ever bigger, is how, and if, it can be managed and controlled – especially from the perspective of trust, sensitivity and respectfulness.

We take the view that its power to bring people and creative processes together, with access to the capabilities offered by such toolboxes is of greatest interest. There may come a time when a single individual can say little that is new about the arts – or anything else. For now, however, is it not, at least, possible that by bringing groups of people together in a wonderfully equipped creative environment that is practically without limits, we can establish a new paradigm for the creative process? And yet: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”